Presentation made to a panel discussion on "Civilian Deaths in Iraq: Quantitative Estimates and Policy Implications," held at the United States Institute for Peace (USIP), Washington DC, 10 Jan 2007.

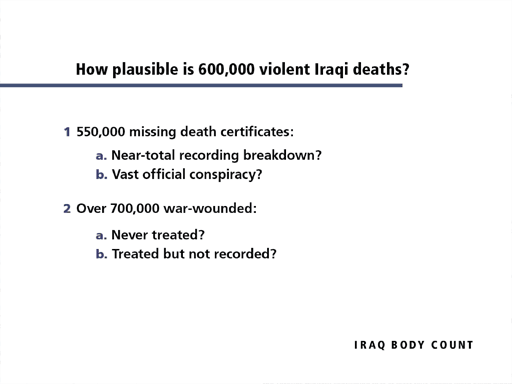

How plausible is 600,000 violent Iraq deaths?

-

550,000 missing death certificates

- Near-total recording breakdown?

- Vast official conspiracy?

-

Over 700,000 war-wounded:

- Never treated?

- Treated but not recorded?

We now turn directly to difficulties with the Lancet “600,000” estimate.

There are two questions. First, how plausible is it that 600,000 is the best estimate of violent deaths since March 2003. Second, if this is not a plausible estimate – what factors could account for the over-estimate. In October 2006, we published a paper on our web-site which outlines five problematic implications of accepting 600,000 as a possible violent death toll.1

1 Reality checks: some responses to the latest Lancet estimate (16 Oct 2006)

2 Borzou Daragahi of the LA Times on their investigations of Iraqi death statistics in local hospitals, cemeteries and morgues PBS Newshour, 11 Oct 2006.

For reasons of time I can only briefly mention two.

Problem One involves death certificates.

Roberts and colleagues report that "92% of households had death certificates for deaths they reported." This would imply that about 550,000 death certificates were issued by local health professionals. Yet figures compiled by the Iraqi Ministry of Health and the Baghdad Morgue identified at most 50,000 violent deaths. That would mean that nine out of ten certificates were never officially recorded as having been issued.

Loss of records on the scale suggested by the Lancet study could only be accounted for by one of two explanations. The first requires there to have been an almost total breakdown of the national bureaucratic recording system right across the country from day one of the occupation to today. And this breakdown would have to have occurred at the same time as local bureaucratic systems functioned almost perfectly, capturing and issuing certificates for almost all of the estimated 600,000 violent deaths. The second explanation would require a perfectly organised and amazingly successful conspiracy, again from day one of the occupation to today, to massively suppress and consistently distort official statistics. What evidence is available from direct investigations at the local level suggest that local and national data are pretty consistent with one another.2

If either of these two explanations were correct, the Iraqi hospitals at the local level who issued all these supposed death certificates must know about these deaths and have records of them, even if nobody else does. And if the official national figures were so wildly low as implied by this Lancet study, any hospital in Iraq should be able to see, and to prove, that they have recorded far more violent deaths - and at every stage of the conflict - than the national figures would suggest. Yet none have noticed or come forward with this evidence sitting under their own noses.

Problem 2 involves injuries.

Knowing what we do about the ratio of injured to killed in conflict, it is inevitable that more, possibly far more, were seriously injured than were killed. The Ministry of Health reported just under 60,000 people as being treated for injuries in hospitals during the two year period from Mid 2004 to mid 2006. Yet, even on the most conservative calculations, Lancet-estimated death totals would imply around 800,000 injuries in that same two year period.

That would imply that over 700,000 Iraqis neither sought nor received any treatment for war-related injuries during that two-year period, and that not a single official, journalist, or NGO, has picked up this fact.

Implausibilities of this sort mount up. When they are put together with a range of sources which suggest a much lower death total than that suggested by the Lancet study, then we have to consider seriously that one or more aspects of the Lancet study’s methodology or data collection has distorted its final estimate of violent deaths very significantly upwards.